The Changeover to Decimal Currency

150 years of dithering

After 150 years of dithering, the final decision to switch to decimal currency was made in a matter of seconds by Jim Callaghan and Harold Wilson. Apparently they discussed the matter during an informal meeting at No 10 Downing Street for less than a minute, and then Harold said, “well why not”. The decision was announced to Parliament on the 1st of March 1966, but of course, all of us who are over 50 know, the changeover was a gradual process that was phased in until D-Day on the 15th February 1971.

Benefit from the changeover

Gross Cash Registers Ltd. was one Hollingbury business that was to benefit from the changeover. Henry Gross had managed to invent a cash till with the ability to switch instantly from £sd to £p. Just along Crowhurst Road from Gross, CVA/Kearney & Trecker Ltd. were also to benefit from the changeover.

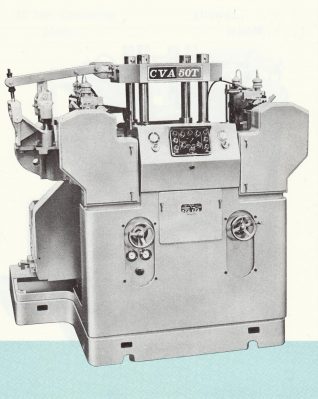

The CVA High Speed Dieing Press

The CVA High Speed Dieing Press had been manufactured at the Upper St James’s Street factory until 1952 when machine production and the associated toolmaking was transferred to the new factory in Crowhurst Road, Hollingbury; now the headquarters of The Evening Argus. There were 5 sizes of the press, which were categorised according to their tonnage. The smallest being 10-ton, then 25, 50, 75 and finally the 100-ton Press. Of course the press was only half of the solution, and on its own was unable to produce anything. The other half was the bespoke press tool, which enabled the desired customer part to be punched, and in many cases formed, out of a flat strip of metal, in high volume.

The Royal Mint

The Royal Mint had been located in the Tower of London and nearby Tower Hill since the 13th Century. Thousands of millions of new coins were required for the changeover; because of this huge increase in required output, it was decided to build a new factory in Wales. In fact 2 buildings were constructed, one for the treatment of “blanks” and a second for “coining” planchets.

Manufacture of coins

The manufacture of coins is not completed by a single blow of a punch. Since ancient times the process was carried out in stages; the final being striking or ‘coining’ between two dies with a hammer. Modern day blanks are produced by the downward stroke of a punch, through a metal strip, into a corresponding shaped die. In preparation for the final coining, blanks are treated in a number of processes; to qualify their exact size, surface finish, hardness and the “rim” is then raised in preparation for the final process. They are then known as planchets, and are ready for coining; where two dies stamp the design and inscription onto both side of the coin, retained within a hardened collar. The collar adds the impression on the coin’s edge as the force of the punch spreads the planchet’s diameter, by 125 microns.

D-Day

Leading up-to D Day so many new decimal coins were required, every organisation involved in their production was at full capacity. While the new Royal Mint in Wales did all the coining, blanks were produced at Tower Hill and some other sub-contractors. One of these sub-contractors was The Mint Birmingham Ltd, which was originally known as Heaton’s Mint. They had been producing coins since 1850 as a private enterprise; separate from, but in cooperation with the Royal Mint.

Order placed

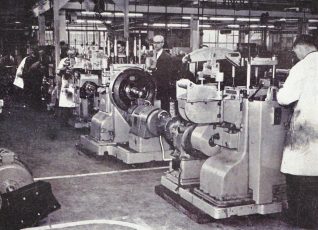

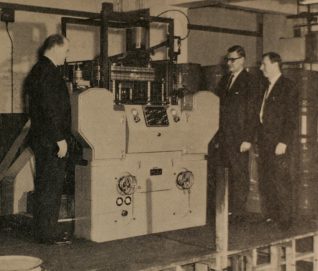

In 1968 orders were placed by The Mint Birmingham with CVA/Kearney & Trecker for a 50-ton High Speed Dieing Press and the associated press tools. The machine was installed early in 1969, and was in production by April, stamping blanks of the new two pence piece. Initially the production capacity was 36,000 blanks per hour, however the capacity was increased by the use of a 12-gang punch, running at 300 strokes per minute, to produce 216,000 blanks per hour; equivalent to £4320.00 per hour. The new two pence piece was first issued by the Royal Mint on 15th February 1971, the day British currency was decimalised.

Schoolboy of the 1960s

As a schoolboy of the 1960’s, I remember two challenges that involved the little loose change we had. Firstly, who could find the oldest dated coin in their pocket? A sure winner would be one pre-dating 1900; they could still be found even in the late 1960s. The second, a few months after New Year celebrations, was who would be the first to find a bright new shiny coin, bearing the current date in his change? As the new decimal coins were introduced it was even more exciting to be the first to find one of the new coins. If you dig around in your pocket now and find a two pence piece of that period, there’s a strong probability that it will be dated 1971. So many millions were produced that there are more in circulation, than that of any other year. If you do find one, there’s also a strong probability that the coin you hold was punched on machinery manufactured in Hollingbury.

Comments about this page

Interesting! Those of us of a certain age will also recall what a rip-off the whole process was as retailers rounded up their prices! To be honest it really passed me by as I had used decimals for so long at Grammar School, but I found that my father, who was a cab driver, seemed overly concerned that change was going to be a problem. I advised him to put the old currency out of his mind completely and accept that mistakes would be made by both sides in the early days. Anyhow, he was happy even after the morning stint, finding it much easier, and less of a hassle to carry money!

I was a school-girl of 15 at the time of the changeover. I remember being rather nervous about it, and asking our maths teacher to devote a lesson to decimalisation. There was a lot of talk about being ripped off as Stefan recalls and, of course, the ’70s was a decade of high inflation. But I, for one, am very glad that currency was made simpler. For a short time I had a Saturday job in a baker’s shop. Adding up the contents of a bag of cakes and bread rolls in £SD in your head on an old-fashioned till (which didn’t add up for you) was no joke!

Having worked in Brighton in engineering all my life, it still amazes me the amount of manufactured products that were attributed to the Brighton and Hove area. Over a thousand steam locomotives to machines that made Airbus wing spars shows the engineering skill base that was developed in the local area. Cash machines, teleprinters, factory switchgear and CNC machine tools were designed and manufactured by local companies, using local skilled tradesmen and engineers; lots of those reputable products were shipped all over the world having the ‘Brighton England’ nameplate attached. You would think products from Brighton’s industrial past would be more linked to Birmingham, Manchester or Newcastle, not a seaside town that for centuries had its roots in fishing and agriculture.

It was during my short period as a bus conductor in 1968 that the first 10p coins were put into circulation, three years ahead of the changeover. Of course they were the same size and weight as the existing florin, just with a different design. When I received the first one I put it safely away in my pocket, imagining that it would become some sort of collector’s item! Poor deluded boy . . . quickly disapprised.

Add a comment about this page